Understanding the SKA Low Layout

The SKA-Low is set to revolutionize the field of 21-cm Cosmology. The first phase of the array will be made up of approximately 130,000 log-periodic antennas laid out in 512 stations of 256 antennas each. It will observe in the frequency range 50 - 350 MHz and is currently under construction in the Murchison Radio Observatory in Western Australia on the traditional lands of the Wajarri Yamaji.

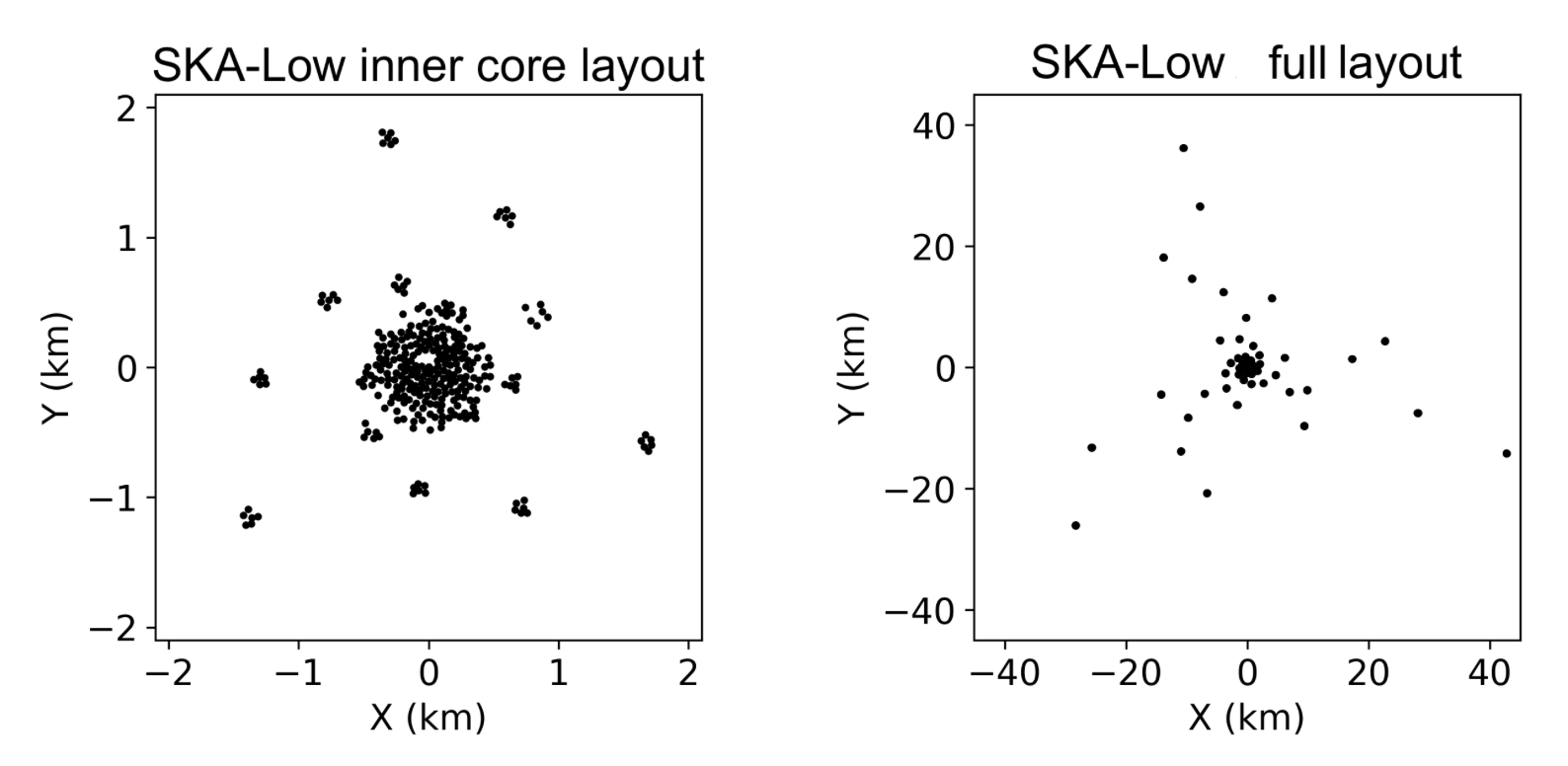

The stations will be laid out in a dense core measuring approximately 1 Km across with further stations distributed along 3 spiral arms. The longest baseline between stations will be 75 Km. The layout is shown below, and the image is taken from here.

The SKA will aim to measure images of the 21-cm signal—often referred to as tomography—as well as measuring the power in the signal on different scales in the sky. Both methods will help researchers understand the distribution of ionizing sources at different epochs and how the Universe was ionized over time. Current telescopes are unable to take images of the signal because of limited baselines and are not as sensitive to the power spectrum as the SKA.

Why long baselines matter for imaging

In order to take images of the 21-cm signal at high redshifts between 6 and 28 researchers need instruments with long baselines. Current arrays like HERA and the MWA are unable to do this but the SKA with its longest baselines of around 75 km will have the resolution on the sky to map the signal from neutral hydrogen. The resolution available to an interferometer is directly related to its longest baseline $D$ by

\[\theta = \frac{\lambda/D}\]where $\lambda$ is wavelength and $\theta$ is in radians. At a frequency of 150 MHz, corresponding to a redshift of $z = \frac{1420}{150}-1 \approx 8.5$, the wavelength $\lambda = 2$m. For a baseline of $D=75 $km this corresponds to a resolution of $\theta = 2.7 \times 10^{-5}$ radians or 5.6 arcseconds. To give this scale the moon is typically around 1800 arcseconds on the night sky. So the long baselines from the SKA will give researchers the resolution needed to image the SKA.

But what about LOFAR?

LOFAR’s longest baseline is around 1000 km, so why can’t we image the signal with LOFAR? This is where multiple factors beyond just baseline length come into play:

Sensitivity: The 21-cm signal is extraordinarily faint—roughly fiver orders of magnitude fainter than foreground emission from our galaxy. While LOFAR has impressive baseline coverage, SKA-Low’s much larger collecting area provides the raw sensitivity needed to detect such a weak signal.

Foreground removal: Paradoxically, LOFAR’s very long baselines can actually make foreground removal harder. The cosmological 21-cm signal has a characteristic smooth frequency structure, while foregrounds vary rapidly with frequency. The challenge is separating these components, which requires specific combinations of baseline lengths—not just the longest possible baselines.

The Power Spectrum: A Different Approach

While imaging provides detailed maps, power spectrum measurements offer a complementary approach that may be more achievable in the near term. The power spectrum measures how strongly the 21-cm signal varies on different angular scales in the sky, without needing to resolve individual features. For example when the first stars start to form there is an increase in power in the 21-cm signal on scales corresponding to the typical scales of galaxies as they illuminate the gas around them.

For power spectrum measurements, the spiral arm layout of SKA-Low becomes crucial. The dense core provides sensitivity to the large-scale variations in the 21-cm signal and the frequency range allows researchers access to rapid variations along the line of sight. Since the foregrounds are smooth in frequency the combination of the dense core and large frequency response gives researchers a clean view of the 21-cm signal.

The compact stations in the core also produce many redundant baselines - pairs of antennas viewing the same signal on the sky. This allows researchers to calibrate the instrument with great precision. Any differences in the signals observed by these baselines will be related to the instrument response and they can be used to better understand how the array sees the sky.

Looking Forward

The SKA-Low’s thoughtful design represents decades of lessons learned from pathfinder instruments. Its combination of long baselines for imaging resolution, large collecting area for sensitivity, and optimized baseline distribution for power spectrum measurements positions it to finally detect and characterize the 21-cm signal from the Epoch of Reionization. As construction progresses, the astronomy community eagerly awaits the moment when we can finally “see” the universe’s first light sources through their ionizing effects on the surrounding neutral hydrogen—opening an entirely new observational window on cosmic dawn.